New England is old, and that’s one of the things I like about it. As most people learned in school, it was one of the first places in North America to be settled by English-speaking people and they left their marks almost everywhere you look. Many of the houses they built are still standing, sometimes with their descendants still living in them. Even where the houses have disintegrated, cellar holes remain.

There’s nothing I like better than to explore the back roads of New England. I keep

DeLorme Atlases of four states on the back seat of my car to guide me if I’m lucky enough to find a few hours and indulge my wanderlust. As family obligations or medical treatment force me to drive to Massachusetts several times a year, I try to work in some side trips whenever possible on the way back. I’ve already taken every possible north to south route where the roads are numbered highways, so now I try to plot back-road detours along each of them. As I investigate those, I find many other intriguing, dead-end side roads too. I intend to examine them all before I die.

Usually, I don’t know how long it’s going to take to explore a road, because I don’t always know where it will lead. Many are not in the

DeLorme Atlas. If my wife happens to be with me, that may limit how far down a particular road I can go or how many side roads I can take before she loses patience. If I’m traveling alone, I usually get home late. She doesn’t worry so much anymore because she knows what I’m likely to be doing. and the next time we’re passing through the area I’d been exploring, I can show her some the best out-of-the-way places I’ve found.

English-speaking people have lived in the area for over four hundred years and they’ve altered the landscape. In addition to houses and fields, they built stone walls which remain long after the house has fallen in and rotted away, and the fields have grown up to forest again. While driving along, I look for old gnarled maple trees near the road as signs for where an old farmhouse may have been located. Usually, I find a cellar hole nearby.

The earliest evidence of human habitation in northern New England goes back only about nine thousand years. Those people were probably very different from the Abenaki and other tribes encountered by European colonists. They were likely nomadic hunters of big herd animals like mammoths and mastodons, and it’s quite possible they hunted those animals to extinction. Otherwise, they left very little evidence of their stay here. Only careful archaeological investigation produces whatever artifacts they left and those can only be seen in museums or private collections. The next inhabitants, eastern woodland Indians, didn’t leave much behind either. There are some pictographs on a cliff in Lovell, some petroglyphs on rocks in the Penobscot, and some shell middens on the coast, but not much else. Their descendants still live in New England, but they’re largely assimilated, living pretty much the way I do.

Also interesting is evidence of the prehuman geology all around us. Maine, actually, is one of the most geologically varied places on earth. At Border’s recently, I purchased

Roadside Geology of Vermont and New Hampshire and I found

Roadside Geology of Maine online. It should be arriving in the mail any day now. I’m already trying my wife’s patience when I pull over to examine road cuts along the highway. Especially interesting are the fresh ones, like those exposed during the recent Maine Turnpike widening.

Many of us around here were forced to learn about geology back in 1988 when the US Department of Energy considered trying to bury high-level nuclear waste in the Sebago Batholith. I never heard of a batholith before that, but I read their literature and found out that a huge mass of granite formed under us millions of years ago when some magma tried to break through the earth’s mantle. It couldn’t quite break out into a volcano and cooled underground instead. The DOE said the batholith, or pluton, extended from Westbrook to Lovell and it was seamless - there were no cracks in it. That was surprising news to the dozens of well drillers who had been boring into it for decades and finding lots of cracks. Otherwise they would not have been able to find any water. Lots of angry New Englanders persuaded the Energy Department to look elsewhere for a nuclear waste dump, but my interest in local geology was reignited.

Ever since, it’s taken me a lot longer to get from place to place in New England, because I have to pull over so much and check out the evidence of history.

Published March, 2004

Saw this one on a hike up Whiting Hill in Lovell, Maine last week. It's white quartz with light brown feldspar - pretty typical for a hilltop in western Maine.

Saw this one on a hike up Whiting Hill in Lovell, Maine last week. It's white quartz with light brown feldspar - pretty typical for a hilltop in western Maine. Here it is closer up. The black outline of weathering around the crystals pleases me.

Here it is closer up. The black outline of weathering around the crystals pleases me. Like to climb over rocks too, especially along Maine's coast. This is part of the bedrock near Biddeford Pool on the southern Maine coast. Maine has some of the most varied geology to be found anywhere on earth. It's not only interesting; it's beautiful. The amateur geologist in me thinks this is sedimentary, metamorphic, turned up 90 degrees and weathered by the surf.

Like to climb over rocks too, especially along Maine's coast. This is part of the bedrock near Biddeford Pool on the southern Maine coast. Maine has some of the most varied geology to be found anywhere on earth. It's not only interesting; it's beautiful. The amateur geologist in me thinks this is sedimentary, metamorphic, turned up 90 degrees and weathered by the surf. This is just a few yards away, but from another age entirely, and that's how Maine bedrock is. This rock heated and swirled more than the one above it.

This is just a few yards away, but from another age entirely, and that's how Maine bedrock is. This rock heated and swirled more than the one above it. Only about four feet away is this one in a seam where iron oxidized, creating dark red staining.

Only about four feet away is this one in a seam where iron oxidized, creating dark red staining. Looks like chemical reactions I don't understand at all are creating different textures as well.

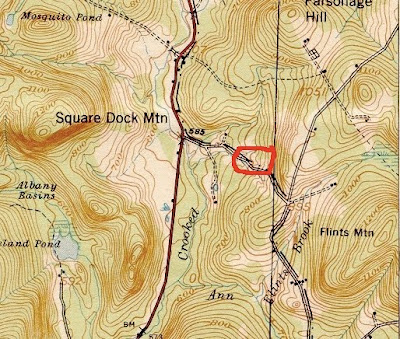

Looks like chemical reactions I don't understand at all are creating different textures as well. Albany, Maine stone wall I found in an abandoned neighborhood last spring.

Albany, Maine stone wall I found in an abandoned neighborhood last spring. Carrickabraghey Castle on Isle of Doagh, Donegal where we visited two years ago. My ancestors built this "keep" - all that remains of the 14th century castle that was about ten times bigger than what you see here.

Carrickabraghey Castle on Isle of Doagh, Donegal where we visited two years ago. My ancestors built this "keep" - all that remains of the 14th century castle that was about ten times bigger than what you see here. It's mostly limestone around that area, but some granitic outcrops are scattered about. Glashedy Island is offshore. Glashedy means "green on top." It's a big rock with ten acres of grass on it. Locals brought sheep out there to graze.

It's mostly limestone around that area, but some granitic outcrops are scattered about. Glashedy Island is offshore. Glashedy means "green on top." It's a big rock with ten acres of grass on it. Locals brought sheep out there to graze. View out to sea from inside the keep. I love the way the limestone weathers inside - so different from the granites and feldspars of Maine. Easier to work as well.

View out to sea from inside the keep. I love the way the limestone weathers inside - so different from the granites and feldspars of Maine. Easier to work as well. View out another window.

View out another window. And another.

And another. And out a door with my wee wife outside.

And out a door with my wee wife outside. And a high window.

And a high window. A long beach nearby deposits weathered rocks in terraces. When waves recede, millions tumble against each other. The sounds they make are as charming to the ear as the polished limestone specimens are to the eye. The wee wife has found a beauty to smuggle home. Ireland won't miss it.

A long beach nearby deposits weathered rocks in terraces. When waves recede, millions tumble against each other. The sounds they make are as charming to the ear as the polished limestone specimens are to the eye. The wee wife has found a beauty to smuggle home. Ireland won't miss it.