There are thousands of poets out there, maybe millions, but very few make any sense to me. It’s possible I’m not sensitive enough, or I’m not bright enough to understand what they’re trying to say. It’s also possible they’re trying too hard, or they’re too artsy and flamboyant. Robert Frost makes sense, but then he wrote of life in rural northern New England where I live. I understand him. Shel Silverstein makes sense. So does Emily Dickenson.

Among Irish poets, the only one I get is William Butler Yeats, and I happened to be in Sligo last month where he wanted his remains buried after he died back in the thirties. He was born in Dublin, raised there, and in England on and off, but his heart was in Sligo where he spent summers. His early poems were esoteric and seemed overly stylish, but his later stuff was much more resonant to my ear, especially The Second Coming. I knew of it from encountering so many of its lines quoted by other writers of both fiction and non-fiction — before I ever knew the words belonged to Yeats.

|

| Sligo last month |

I don’t know where or when I heard it initially, but the line that struck me first was:

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Who are the best these days? Who are the worst? Well, the best, I think, would be those who take a long view of the human condition. They know something of history — what has worked and what has failed over the centuries, over millennia even. They don’t know all of history; nobody does, but they perceive an outline of how we humans have behaved in times of plenty and in times of want. They understand what governmental systems have been applied and what resulted. Others who see only what’s in front of them — who know only what has occurred during the last few years of their own lifetime. They are the ones full of passionate intensity today, a century after Yeats studied their counterparts.

|

| Sligo last month |

Do the best lack conviction? Maybe, or perhaps they have tried long to reason with the passionately and intensely ignorant with little result. Maybe they’ve given up trying to persuade and are saving their energy for when, as Yeats puts it:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.

Yeats was born to English privilege. His ancestors were part of Ireland’s protestant ascendancy. He was classically educated but his loyalties were divided between his British colonial ancestors and the Celtic Irish among whom he lived, and to whom he related most. Ultimately, he sided with them against Ireland’s British overlords. He was an active participant in Irish Literary revival but stayed on the sidelines during the 1916 Easter Rebellion and ensuing struggle. He sympathized with the cause, but not with the violence used to gain independence.

Mostly agnostic, Yeats disdained Roman Catholicism but related to ancient Irish mysticism. While most Irish of his time were comfortable with a blend of the two, Yeats was not. He related much more to pre-Christian Gaelic culture and that influenced his poetry. The Great War had just ended when he published The Second Coming in 1919, exactly 100 years ago. The 1916 Rebellion was followed by the Irish Civil War waged until 1922 with the Russian Revolution in the middle of all that as well. Things were indeed falling apart in Yeats’ world.

The great love of Yeats’ life, the actress Maude Gonne, was caught up in both Catholicism and violent rebellion against the British. Yeats proposed to her four times and was rejected four times. She instead married Irish Revolutionary John McBride who was executed by the British after she divorced him, but Yeats carried a torch forever after. He had love affairs and a marriage that produced children, but his personal life was as confused as his theology.

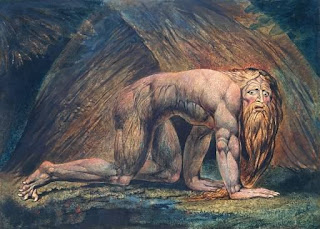

The Second Coming is apocalyptic but vague. He evokes Christian imagery but blends it with ominous images of The Sphinx. Rather than a triumphant return of Jesus Christ, Yeats sees something menacing:

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;

A shape with Lion body and the head of a man…

…And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Both Christians and secularists today point to signs of an approaching apocalypse, but Yeats had much more reason to suspect it: World War I, violent rebellions in Ireland and Russia, the Spanish Flu killing tens of millions — all that was happening as he wrote The Second Coming. 2019 seems placid compared to 1919.