We buried her Tuesday.

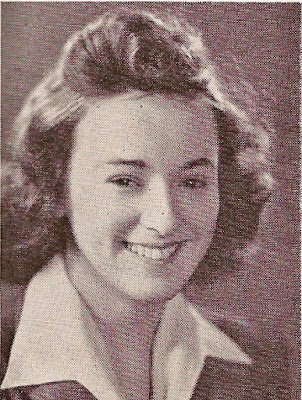

She became Mary McLaughlin in 1942. Her boyfriend, Mac, came back to Boston briefly on leave from the US Navy. She said later that she didn’t really want to elope with him but he was persistent and she gave in. Mac recognized what a gem Mary Haggerty was and he didn’t want to lose her. She was exceedingly pretty and he knew other men would do their best to win her.

Elopements like Mary’s were common during World War II, and Mac sailed off a day later. As Mrs. McLaughlin, she moved several times to various port cities on the east and west coasts —wherever Mac’s ship was sent. She’d find a secretarial job and a room. When his ship was deployed to England she waited for him. After D-Day when his ship was deployed to the Pacific, she waited for him in San Francisco. She had her first child in 1946 and seven more after that until 1963. It was the baby boom.

Mary had been a single girl for eighteen years. She was a wife for thirty-five years before Mac died in 1977. She was a widow for forty-three years. She was a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother for fifty-four years. Her eight children called her Ma. Her twenty-nine grandchildren called her Ma and so did all their spouses. Her forty-two great-grandchildren called her Ma, and eventually that’s how she thought of herself: as Ma.

As matriarch for an extended family of more than eighty people, she endeavored to pass along the faith she had inherited, and did so by embodying it. Shortly after being widowed, she used Mac's life insurance to buy an old farmhouse in Lovell and fix it up. She recalled many happy summer days in the country with her own grandmother and wanted the same for her grandchildren. For thirty-two years, she provided those memories before finally going into assisted living five years ago at ninety-one.

In the year 2000, Ma invited her children to accompany her on a trip to the Holy Land. All were deeply affected by the experience of walking the paths Jesus Himself walked two thousand years before. Whenever they heard gospel readings after that, they could remember being in each of the places where His preaching and His miracles actually took place.

As Ma went into hospice at ninety-six, her extended family opened a forum on Whats App where her many offspring posted remembrances of what she left them: her love and her faith in God, both of which she lived out seamlessly. One said:

“Ma we owe everything we have to you, the way we conduct ourselves, treat other human beings and our belief in god is all owed to you. Through your pure kindness, hard work and patience you’ve made us all good human beings who will teach our kids and grandkids forever after you meet God.”

Another said:

“It’s amazing to reflect on all you have taught me and our family about love. You taught us all with your whole life — by the way you lived, by the conversations you had, and in all of your relationships with us. You taught us in big and small ways. These have impacted my life in important ways at various times. I know they will continue to do so long after today.”

Another said:

“When we would visit, I remember Ma would let us kids into her bed early in the morning. With her eyes closed we would say prayers, then she would tell us stories. They always started with a blueberry patch. When my children wanted to read the same book for the thirty-fifth time, I closed my eyes and started into the same blueberry patch stories. Love you Ma.”

Another said:

“As a kid when I asked you why you moved to Maine, you spoke of making memories for your grandchildren similar to your own childhood — of a grandmother in the woods. I think you achieved that goal and more. You certainly made an imprint on all of us, Ma. While I wish those woods were a little closer to Massachusetts, I’ll never forget all the time spent with you up there! Though I’m on the tail end of the grandkid lineup (somewhere in the 30s I believe), I felt no less special. I think you made everyone feel that way. You have a unique gift to draw others in and make them feel genuinely loved. Your sincere love for others, simple joy, and obvious faith are what I’ll always admire most about you.”

All the grandchildren commented on the refrigerator in Ma’s kitchen which was completely covered on two sides with wallet-sized, school pictures of them and their many cousins. Several also mentioned the giant freezer in the basement. Mary and Mac had each grown up poor during the Great Depression and threw nothing away that wasn’t thoroughly worn out. Mac sometimes went hungry as a child so, after they married and children came, they purchased a huge chest freezer. Mac kept it full bygoing food-shopping every Saturday. He negotiated with bakery managers to buy day-old bread — fifty loaves at a time — for a nickel each. He made sure his children would never know hunger as he did. After Mac died, Ma brought that freezer with her up to Maine.

One grandchild said: “I still think of you when I smell bacon, as that’s usually the smell that woke me up in the morning in the Blue Room. I remember drinking orange juice from your recycled juice glasses and making sandwiches to take to Kezar [Lake] made out of bread that was in your freezer (probably) longer than I’d been alive. I, too, remember crawling into your bed and praying along to the radio rosary. I’ll admit I thought the rosary was painfully boring, but I loved snuggling in close with you in your warm bed. And now, many of my daily rosaries are offered for you!”

All who loved Ma worried that, during Covid, she might have to die alone. Her daughters looked for a hospice that would allow loved ones to visit, and finally found one nine days before she passed. As the testimonies poured in on What’s App, they were read to her. She heard the above tributes and many others like them as she waited for Jesus to call her home. Two of her daughters were holding her hands and praying with her as she passed on to eternal life. For that, we’re all grateful.

Few are as prepared for death as Ma was, and for the past few years she wondered aloud why she was living so long. During that time she told some of her children what was most important to her besides her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. First of those things was her church work, like serving on the building committee for the Elizabeth Ann Seton Church; serving as secretary for the Church Council; volunteering at the Dinner Bell (the local soup kitchen); working at the Lighthouse Pregnancy Crisis Center whose mission was to provide practical, life-affirming, alternatives to abortion; and serving as Eucharistic Minister and taking it to shut-ins.

For decades she was very active with the Pro-Life Movement at many levels, believing strongly that: “We have to promote the dignity of the human person and the Sanctity of Human Life.” Born a Boston-Irish-Catholic-Democrat as so many of her generation in Massachusetts were, she had to leave the Democrat Party when it became the party of abortion. She became a Reagan Democrat, and eventually a Republican. The Party had changed, not her. For years she haunted pro-abortion Democrats like Congressman, then Senator, then Presidential candidate, Paul Tsongas. Then she haunted his counterparts in Maine. Ma never relented in her fight against abortion.

Nearly all families are touched by alcoholism, but especially the Irish. All her ancestors came from there and do did Mac’s. She understood what damage alcoholism did to families and she became active in Al Anon, a program for anyone who loves an alcoholic. She sponsored many in both Massachusetts and Maine and started an Alateen program in Fryeburg. Through these organizations she touched hundreds of others in whatever community she lived.

Being as involved as she was in so many activities meant a lot of driving on rural roads in western Maine. Ma liked to get where she was going quickly and was often pulled over for speeding, even into her eighties. “I’d roll down the window and smile sweetly at them with my white, old lady hair and they’d let me go,” she said. More than one grandchild remembered being with her when she went too fast for the slippery conditions and she’d yell, “Hold on kids!” as she went into the ditch. She damaged her cars a few times but no one ever got hurt. It was like she had divine protection.

Two great-granddaughters were named for Ma and there are just too many moving grandchildren posts to list here, but one more:

“I was just thinking about all the special memories I have of you as I was holding Danny and putting him down for a nap. Many are of your house in Maine and all the great times we had there- I loved your fridge full of pictures! That’s what I thought of first. It was always fun to find yourself and see all your cousins (and there are a lot of them)! The best was climbing out the kitchen window to the sun porch- that was a pretty big deal to a kid. The fire wood chute was also exciting! Could I fit down it? I wished we had one in our house. I remember your aloe plant in the upstairs hall and how we would use it for sunburns. I remember crawling into bed with you in the early morning and I thought your mattress was soooo comfy! I enjoyed playing card games with you in the dining room. I remember all your braided rugs. The creaky stairs. It was fun picking carrots from your garden and finding glass bottles in the woods for your collection. Swimming, hiking, and being with cousins was the best! Watching tv with you as you crocheted on your chair. Lately, I’ve really enjoyed our phone conversations and I’m going to miss them a lot. You have such wisdom and faith and I’ve learned so much from you. “You sound so happy!” — that’s what you would always say when we spoke. It’s been so nice sharing stories about the kids with you. How did you ever remember all the grandkids’ names? Probably because you prayed for them all every night. I told you last week Luke didn’t realize (because he’s so absent minded) that he put his clean underwear right over the dirty ones and you laughed and laughed! It was the best. I hadn’t heard you laugh like that in a while!”

A daughter who was with Ma near the end reported several things she said. Among them were:

I need Jesus.

I need the Eucharist.

I need to see my children.

I'm so happy.

I love seeing your face.

I feel the love.

Jesus I love you above all things.

And one of the prayers her daughter said with Ma during her last days included a quote from 17th century scientist and mathematician Blaise Pascal:

“Reflect on death in Jesus Christ, not without Him. Without Jesus Christ death would be dreadful, alarming, a terror of nature. In Jesus Christ it is fair and lovely, it is good and holy, it is the joy of the saints.”