Even then, it would be best to answer by telling a story. It could be from your own history or part of someone else’s that contains insight. As a teacher I was charged with passing on designated slices of U.S. History to students. With a textbook, any literate person with attentive scholars could, theoretically, do that. Answering perceptive questions, however, requires broader knowledge than the textbook imparts. Offering different perspectives on historical events does too.

Some historical perspective is necessary for wisdom. It may only be of personal and family history with keen observation of a small community lived in during one lifetime. The same patterns can be detected in a small place as can be seen in the wider world over a longer time. No one, not even the most learned historian, knows it all. Will and Ariel Durant, a 20th century husband/wife team of historians wrote “The Story of Civilization” which ran to four million words in eleven volumes. They chronicled up to about the 1930s and had plans to extend the series, but they died.

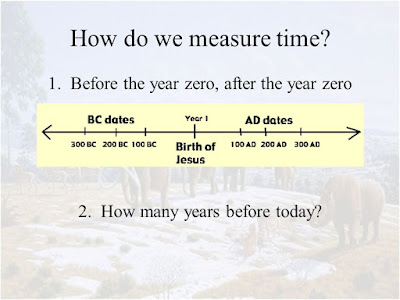

I’m old enough to remember the buzz around publication of R. Buckminister Fuller’s book “Critical Path” in which he postulated that the sum total of all human knowledge gathered by the year 1 AD took fifteen centuries to double. Then it took only 250 years to double again, and only 50 years to double yet again. Now it takes only one or two years. “Knowledge is power,” said Francis Bacon. If he and Fuller were both right, humans have been getting very powerful very fast, but has there been a commensurate accumulation of wisdom?

Doesn’t seem like it from where I sit. Maybe it’s all around me but I lack sagacity to recognize it. If wisdom has been piling up it’s not disseminating, perhaps because too few people are disposed to take it in. I cannot recall the last time I tried looking up something on the worldwide web and didn’t find information about it. We can access knowledge on the internet, but what kind of alchemy is required to convert it to wisdom?

Some religious traditions indicate that wisdom can be divinely granted. In the Old Testament God told Solomon to ask for anything and he requested wisdom. Impressed, God then granted him other gifts. In the New Testament Book of James it says anyone may ask God for wisdom and get it. Other religions suggest it’s attained through meditation or reincarnation. The Old Testament’s Book of Wisdom, whose author is unknown, uses female pronouns when referring to it. Then he or she portrays wisdom as an amalgam of other virtues, especially humility.

So, when as a wise elder you’re asked a difficult, timeless question by a grandchild, it’s okay to humbly answer by saying: “I don’t know.”